I’m in the Navajo Nation, the largest Indian reservation in America. I’m sitting on a tan-and-white pinto called Bandit in Monument Valley. We’re following our guide Larry Lynch. Larry isn’t one of the Irish Lynches. Hardly. His great-grandfather was one of the reservation’s early hanging judges.

There’s a strong wind blowing and some menacing black clouds dancing in formation to the east. Larry is shouting prayers in Navajo to Tó Neinilii, the rain god who appears to be listening; the wind changes direction. It should be a cause to celebrate, to rope a bull or at least coax Bandit to gallop eastward and chase the storm well and truly out of town. But I don’t do either. Thing is, I want to go home.

What is it about grey, horizon-less London that’s pulling me away from the big blue skies of northern Arizona, its mitten-shaped buttes the colour of jack -o’-lanterns and the enigmatic Diné bizaad (Navajo language)? Is it the romanticising of England, the kind of nostalgie de la boue that would get the writer Bill Bryson waxing eloquent every time he passed a rancid-smelling fish and chips shop in the rain? Or maybe it’s the next lockdown – the one you and I know is coming as sure as there will be death and taxes.

To tell you the truth, I think it’s the ghosts beckoning. There aren’t many here in the New World and, as some of you might remember, I spend a fair amount of time with them. Oh sure, we’ve got plenty of skeletons here, but ghosts are at a premium. So, a click not of red slippers but a pair of beat-up old riding boots, and I’m flying across the endless prairie, punctuated every 10 miles or so by a silo and a suicidal-looking family. Then we’re over anointed New England and across the raging North Atlantic to an older version of same. Home.

Through the front door and up the stairs and I’m soon in the master bedroom, about to take my seat by the window. It’s a place I spent a lot of time in exploring the world within my view during the first lockdown last year. But now it’s to sew. Yes, for real. A button is missing from a couple of my husband Mike Rothschild’s shirts. It’s something that seems to bother me more than him.

I lower myself into the seat – rush, carved, Filipino, a bit wobbly after 100 years or so – and almost hit the ceiling. Pins and needles. Jesus, did I leave my sewing paraphernalia on the seat? I bend my mind but can only recall stitching here last April – or so my diary tells me. Then the light bulb goes on (or more accurately a taper is lit). ‘That bloody Maggie,’ I mumble to myself.

A dark-haired woman in her mid-30s walks into the room. She’s dressed in her Sunday best – all bonnet and bustle. It must be time for church, and Mike has clearly gone out to the shops; in general, ghosts don’t like being around nonbelievers. ‘Sir?’ she asks.

I remain standing, rubbing my derrière. ‘Isn’t the Ghost of Christmas Past a bit early this year,’ I ask sarcastically, ‘or are you just very late?’

Maggie shoots me a look that would have made Margaret Thatcher quake. ‘I’ve told you, sir, we are spirits here – not ghosts. I would very much appreciate it if you would lose that nomenclature once and for all.’

‘But what about Mr Dickens?’ I ask her. ‘That was the term he used to describe his trio of Yuletide visitors, was it not?’

‘I shall not hear more, sir, of that so-called writer, nor shall I make mention of him. Well, perhaps only to say that he gave us all such a bad name that we gave him one too. You can guess it by dropping the last few letters of his surname.’ Ouch. Maggie (and much of the rest of the spirit world, it would appear) was no fan of Charles Dickens.

‘That’s all well and good,’ I begin, ‘but it does not explain why you continue to make yourself at home here, use my belongings and then leave them in places where they do not belong. Good God, anyone would think you owned the place, that you really belonged here.’

She winces at my profanity and looks crestfallen. ‘But I do, sir’ she says. ‘Just like you.’

And now it’s my turn to feel a bit deflated. Belong? Did I ever belong to anywhere? I’ve never been partial to group participation, to flash mobs, to benefit concerts where everyone lights matches or turns on their mobile phone flashlights and sings along in unison. I’ve always felt like something of a mayfly on the surface looking down. But maybe, just maybe, it’s time to take the plunge.

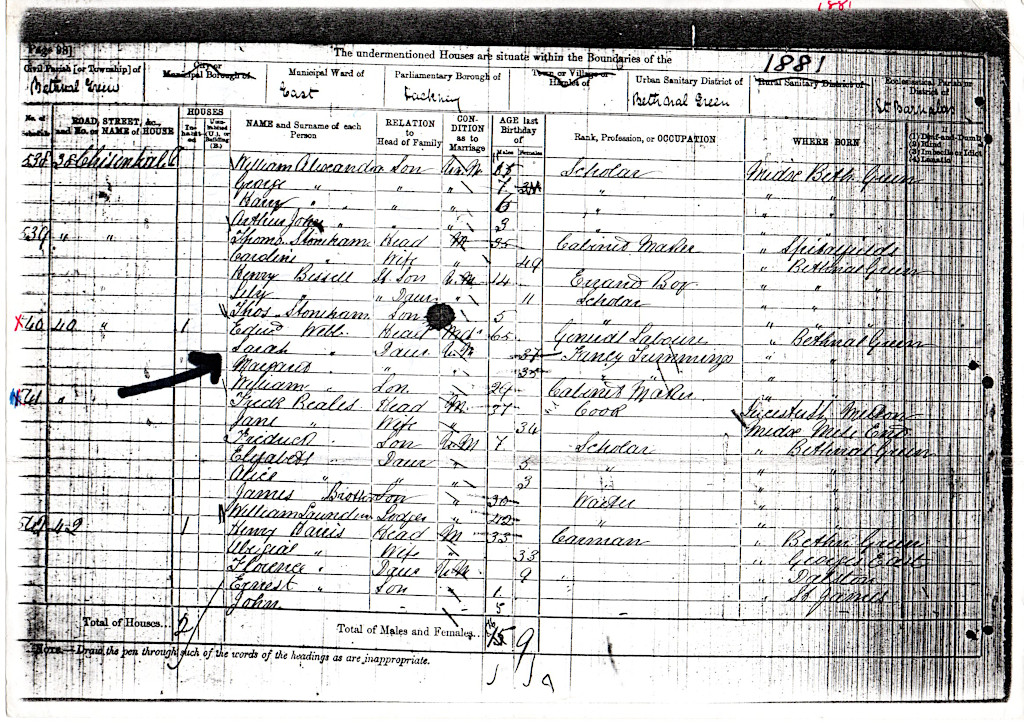

In some ways Maggie belongs here even more than me – after all she got here first. For her it’s 1881 and Miss Margaret (‘Maggie’ to me) Webb has lived at 40 Chisenhale Road in Bow (she calls it Bethnal Green) since the house went up nine years before and where she takes in piecework as a fancy trimmer. The head of household is Maggie’s father, Edward, a 65-year-old general labourer who spends more time at the Unicorn pub on Vivian Road than at home. Residing here too are Maggie’s older (by two years) sister, Sarah, another fancy trimmer who Maggie loathes – I haven’t learned why – and her younger brother, Willie, age 29, a cabinetmaker who she adores. Willie works for Mr Tom Stoneham at No 39, whose wife, Caroline, is 14 years his senior – the subject of endless gossip on Chisenhale Road. Well, until recently. That was all side-lined in February of that year when Miss Angela Burdett-Coutts, the ultra-rich 67-year-old heiress and philanthropist who built the monumental drinking fountain for the East End poor in Victoria Park around the corner, married her American secretary, Mr William Bartlett aged 29. A difference of 38 years, Maggie points out, adding with a gasp that Miss Burdett-Coutts lost two-thirds of her inheritance as her stepmother’s will banned her from marrying a foreigner and – double gasp – Mr Bartlett, soon to be a Conservative Member of Parliament, took on Miss Burdett-Coutts’ surname.

‘It’s like a fairy tale,’ Maggie sighs.

In fact, none of the Webb children have been very successful in love, which seems to bother Maggie, judging from occasional comments about being alone. Once I tried to cheer her up by suggesting that there was surely a ‘man in the future’ but had to quickly swerve to avoid that pothole. She knew that I knew that she knew her future was long, long past.

So, I remind myself to think inclusive, especially now that she’s feeling fragile. I give Maggie a theatrical bow and hold out my hand. ‘May I walk you to church, my fair lady?’ I ask. She smiles broadly and takes my arm. And as we begin to walk down Chisenhale Road heading toward Roman Road and her church, Maggie begins to hum. I recognize the song immediately and look at her, my eyebrows raised in question ‘You are not my only eyes into the future, sir. There have been many. And one day – God willing – you will have your own, too.’

And so we begin to sing – I mean really sing, as in belting out – as we twirl around the lampposts:

I have often walked on this street before

But the pavement always stayed beneath my feet before

All at once am I several stories high

Knowing I'm on the street where you live

Are there lilac trees in the heart of town

Can you hear a lark in any other part of town?

Does enchantment pour out of every door

No, it's just on the street where you live

For oh, the towering feeling

Just to know somehow you are near

The overpowering feeling

That any second you may suddenly appear

People stop and stare, they don't bother me

For there's nowhere else on earth

That I would rather be

Let the time go by, I won't care if I

Can be here on the street where you live

And with that Maggie walks past the local C of E vicar into the church porch and disappears. Father Ryan looks at me quizzically, about to ask me why I am singing and appear to be following someone who isn’t there. I cut him off before he can ask. ‘I’m Catholic, remember?’

I haven’t seen much of Maggie since that Sunday morning. Thing is, Christmas is coming, and she was never very keen on it. Is it a family thing? Or maybe like Queen Victoria, she’s still mourning Prince Albert two decades on. Most likely she stays away to avoid hearing Yuletide mention of Mr Dick and his three ghosts – sorry, Maggie – spirits. She’ll be back, though. And that’s a fact.