I’m looking out the window to the street below. One of those annoying yappy dogs is dragging its owner on an exceptionally long leash. Everything about it bugs me, including its colouring (which, by the way, matches the oblivious owner’s hair). ‘That dog has a brown head and a black body,’ I hear a voice say. I jump and turn but see no one. But I know who is speaking.

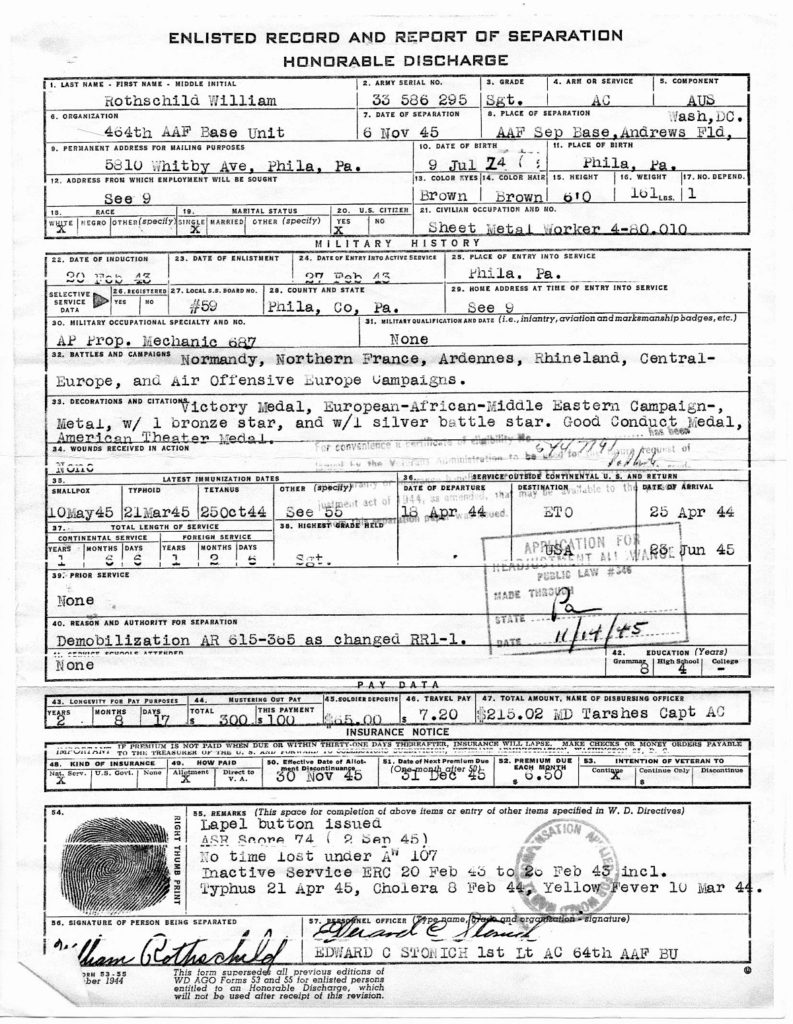

William Wolfbaer Rothschild came along with my husband, Mike. Part of the package and how not? He was his father. Cool middle name, huh? I sort of thought it matched him as well as that dog’s fur did the owner’s hair. Different, weird, Germanic (his father apparently had eyes as blue and hair as blond as a Prussian’s). Mike didn’t think so, though – not the cool part. Isn’t that always the case? Parents embarrass kids at home while the outsiders can’t seem to get enough.

And so it was with me and Bill, the guy who took on the ‘second father’ mantle almost three years to the day after mine had died. Oh, those two did share a few things. Both had immigrant parents arriving in America in the early 20th century. Each had lost his father at a young age and both were politically left of centre. But the similarities ended there. Bill was Jewish and an atheist; my Roman Catholic father would have found the latter strange, even frightening. Bill was a university graduate and a teacher while my bus driver father was self-taught. And though my father could do most everything around the house – electrics, basic plumbing, a little bit of woodwork – and had passed most of it on to me, he was an amateur. Bill had taught shop to schoolkids in Philadelphia and was an expert in all things DIY. It was a match made in heaven (a word he really didn’t have much time for).

Our favourite day out was spent browsing through Home Depot — the American version of B&Q — and debating the merits of one make of chisel over another, discussing the gradients of sandpaper and arguing whether ‘quality ply’ was an oxymoron. Sometimes Mike came along for the ride, but we didn’t like that much. He’d get bored quickly – and we’d only reached aisle 3 of 12 by then! – and start moaning about lunch. Cheesesteaks, hoagies, Rizzo’s pizza – everything was good with Bill and ‘the treifer the better,’ he’d say, using the Yiddish word for non-kosher food.

He and his wife (and Mike’s mother) Beulah, who also did not share his enthusiasm for DIY, was religious and kept kosher, visited us everywhere we lived. This meant we had to borrow a wheelbarrow and load up at the closest kosher food shops to feed these two ‘starving Armenians’ (as Bill would put it). That was no mean feat in Hong Kong, but a lot easier in Budapest and just a hop, skip and a schlep to Stamford Hill in London. But the stories and out-of-the-blue observations – ‘She was a handsome woman who had the misfortune of being hit and killed by a bus,’ he once said of an aunt – were worth all the shopping, cooking and the cleaning.

Bill had been based in Norfolk as an aircraft mechanic for the US army airborne for the last two-and-a-half years of the War, servicing the workhorse B-24 Liberators. He almost never mentioned that time but then on the 50th anniversary of VE Day he came to the dinner table wearing his medals. So, when Bill and Beulah came to visit us at our old mill house in Essex not long afterward, we decided to take him down memory lane.

We didn’t need a map. As we approached the northern border of Suffolk, Bill shouted: ‘Stop, stop, we’re here.’ I saw only wheat fields and said so. But we found ourselves on an overgrown tarmac, all that remained of Metfield Airfield, home to the 491st Bombardment Group of the 2nd Air Division until a massive explosion at the base’s bomb dump in July 1944 killed six soldiers and forced a move to North Pickenham Airfield in Norfolk. It was less than a week after Bill’s 20th birthday. North Pickenham was equally anticlimactic – just a nondescript modern business park of corrugated metal buildings. But Bill knew where he was and immediately recognised some original Quonset (Nissan) huts and a B-24 tire being used as an ornamental planter at the entrance. I had to pull him from the local pub later that afternoon after several hours’ reminiscing with some of the old boys propped up at the bar.

Bill was still unusually chatty when we got home and seemed more anxious than ever to tell his story. ‘That FDR was such a darn tightwad,’ he said of the late president whom I’d always assumed was his hero. ‘He didn’t want a scrap of metal left behind and had us fly all those wrecks home.’ The B-24s could fly long-range – they were the first America aircraft to routinely cross the Atlantic – but they were slow. The one Bill travelled home in was in particularly bad shape and had to fly low. Midway across the Atlantic he smelled fuel and climbed out onto the wheel-casing to investigate the leak, staring at the grey ocean below. ‘I’d rigged up a flashlight attached to my helmet that was wired to a dry cell in my pocket,’ he told us. ‘I was petrified the spark was going to blow us all to kingdom come.’ I looked at him incredulously. ‘Everyone did stuff like that,’ he said. ‘There was a war on.’ But not everyone made it home. The 2nd Air Division alone lost more than 1450 of these workhorses and 6700 men.

My relationship with Bill continued for another decade or so, but the roles were reversed each time I visited him at home in Philadelphia. No longer was I in a supporting role but the lead actor when we put up the storm windows for winter or cleaned out a blocked drain in the cellar. I thought, ‘This is how it passes from a teacher and father to a pupil and son.’

When we got the news we’d been expecting but dreading, it was a frigid February morning and London was bracing for its heaviest snowfall in almost two decades. We did make it in time – not before abandoning the snowbound taxi on the M23 and sliding down an icy ramp road into Gatwick airport – to say goodbye and lay him to rest under shovelful after shovelful of hard black Pennsylvanian soil. Then in the car on the way to sit shiva with lox and bagels and covered mirrors, and then the inescapable airport and London and life post-Bill, I glanced upward. There was a kite, one of those really old-fashioned geometric ones with a long tail. It was a on a broken string and appeared to be racing into the wild blue yonder, to heaven itself.

And I wondered: had Bill changed his mind?

This is London from my window. Look out yours from time to time. You’ll be astonished at what you see.