I’m helping my husband, Michael Rothschild, re-arrange the window boxes in our bedroom upstairs. I do the lifting, not the nurturing; my thumbs are black. Two doors to the east scaffolders are erecting staging across our neighbour’s roof. Yet another loft conversion is in progress. The workmen are Polish.

I’m distracted not so much by the profuse use of the `k-word’ (use your imagination) but by the smell of their lunch – bigos, sauerkraut and beetroot. Sweet, sour, porky. The holy trinity of Polish aromas. And as if I’d just nibbled on a Proust madeleine, I am transported. Shop queues, shortages, empty shelves, panic buying, a depreciating currency. But big and generous hearts that still manage to dispense so much love even in a time of crisis… No, I’m no longer in Bow, East London. I am flying.

They say the past is another country, but I’ve always found it to be as close as my own backyard. I can remember as if it were yesterday what card games I played with my fellow passengers and what we ate and drank on that long train journey from the Gare du Nord in Paris on a warm Saturday afternoon way back in late September 1975.

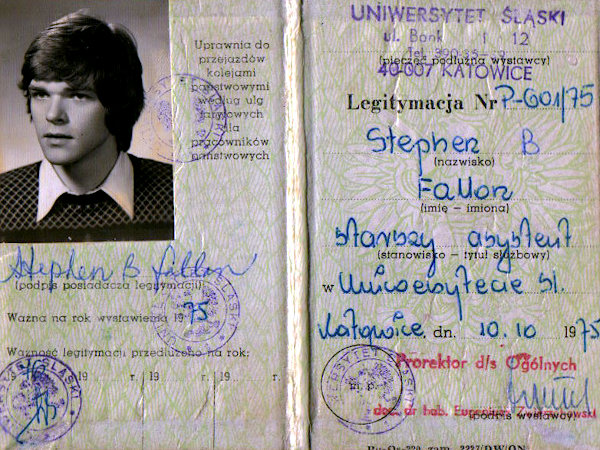

I was on my way to the People’s Republic of Poland to begin a year of teaching English at the University of Silesia near Katowice, a then soot-coated industrial city 80km northwest of Kraków. A fresh-faced American college grad with insatiable wanderlust and a desire to have more than just a peek behind the `Iron Curtain’, I would learn a lot over the coming year. World War II and its horrors were not a distant memory as they were in the affluent West; the arms of strap-hangers on trams with their tattooed numbers were a frequent reminder. Communism, at least the Soviet variety, was a sham. Yes, you really could live with nothing – if nothing was available.

I knew I was being watched (or at least listened in on) from the very start. As I lay in bed at the lecturers’ residence the morning after my arrival, a woman let herself into my tiny studio apartment, waved rather nonchalantly and removed my telephone. She returned it about an hour later. At a teachers’ meeting several months later, the head of department, Janusz Arabski, with whom I had had a falling out over extra (and unpaid) work, snidely remarked that he’d have to speak in English as `Steve’s Polish stinks.’ `How do you know, Janusz?’ I asked. `Have you been eavesdropping on me by telephone again?’ The icy silence was telling.

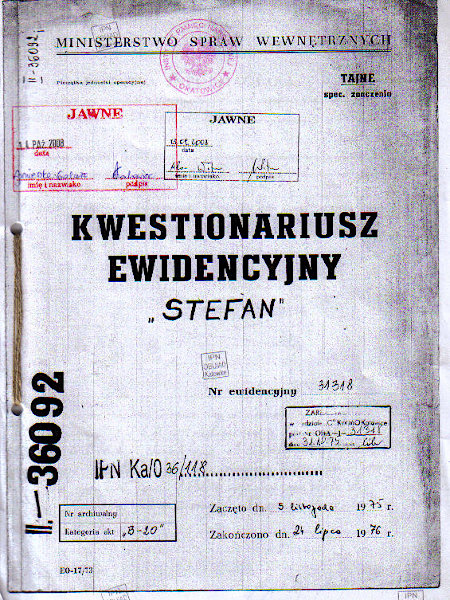

But until I saw the film The Lives of Others some three decades later about the state monitoring of East Germans, I never dreamed the SB – the Polish secret police – would bother keeping a dossier on a gówniarz (squirt) like me. In the summer of 2007, while updating the Lonely Planet guidebook to Poland, I visited the ultra-modern offices of the IPN, the `Institute of National Remembrance’, in Katowice. `Would I please list the reasons why I think I had a file?’ `Let’s see,’ I said. `Poland, 1975, American, gay… I’m not certain there will be one on me.’ The young receptionist looked at me. `Pan (Mr) Fallon,’ she said sharply, `you most certainly will have a file’.

About 18 months later my file arrived in the post in Bow, East London. I don’t know what I was expecting, but it wasn’t this Valentine from the spy who loved me, full of platitudes and glaring mistakes. `Mr Fallon has a bubbly personality, is very presentable’ and hangs out with Lidia Dylong (I knew a Sabina Dylong), and is having an affair with Barbara Latta (who?) though his best friend Jolanta Kazoń `is in love with him’. (Jola now denies that from her yacht in Australia but I kinda believe the informer.) Nothing about me cruising the train station in the wee hours… The SB were clearly not the efficient East German Stasi.

My informers bore the pseudonyms `Ewa’, `Zbyszek’ and, in what must be the Polish `butt’ of all jokes, `Arski’. I had strong suspicions about one but didn’t give the identities of this ghostly trio much thought. Then about six months later another letter arrived from the IPN, this time announcing `Decision 42/09: To identify the persons who passed information to the state’s security organs about the applicant.’

In it the IPN refused to reveal the real names of `Ewa’ and `Zbyszek’ because they could not be `unequivocally’ linked to me. The last was a different story altogether. As I suspected, `Arski’ was identified as Janusz Arabski, my former boss and nemesis.

My file never caused me any difficulty or hardship; having one really just makes for a good tale to tell. But what damage did `Arski’ and his ilk do to my colleagues, my students, my friends? One was refused a place in university and a passport in 1973, at a time when everyone was allowed to travel.

I tracked Arabski down – he was still teaching at the same university. We exchanged emails and then had a 30-minute recorded telephone conversation. He refuted almost everything – even the `unambiguous’ (the IPN’s words) link to `Arski’ – except for having provided the SB with basic information about foreign lecturers like me.

Arabski even seemed to suggest we shared space in the same boat. `When I lectured in the USA from 1980 to 1983, I know that the American services collected information on me, too. Who supplied it, I do not know and I do not care.’

And then, in a fiasco that would have made Richard Nixon proud, I pushed the erase button. Well I think I did and now I don’t know what I said. What I really mean to say is I don’t want to know what I think I said then. Maybe I was judgmental: `Thing is, I do care, `Arski’ – Arabski – and now I know.’ Or maybe I said something like: `You know, I wonder what I would have done in those circumstances. So much has changed…’ I’ve really managed to confuse things and get everything into a muddle.

Someone very wise recently said: ` I hope in the years to come everyone will be able to take pride in how they responded to this challenge. The pride in who we are is not a part of our past, it defines our present and our future too.’

OK, God, so here’s the deal. When we all awake from this nightmare, if you promise to make the world a better place for everyone, I’ll be a better person.

And then I think: Oh, have I put things back to front again?

This is London from my window. Look out yours from time to time. You’ll be astonished at what you see.