Like all of us, I’m housebound. In a bid to allay cabin fever and death by boredom, I’ve taken a front-row seat by the window. With a tip of the chapeau to Colette, who wrote Paris de Ma Fenêtre (Paris from My Window) from her apartment on the Place du Palais Royal during the German occupation of Paris in WWII, I’ll begin my random musings on the city from one small corner of London during the `occupation’ by the coronavirus COVID-19.

My husband Mike Rothschild and I live in a mid-Victorian three-story terrace house in Bow in East London. It is well-situated. To the north it backs onto to the Hertford Union Canal linking the Regent’s Canal and Lee River just below Victoria Park. To the south are the towers of Canary Wharf. If I crane my neck and turn east, I can just about see the former Olympic Stadium and the Orbit. As I walk to the bus stop, the Gherkin and several other City buildings peek out from the west.

The house was built in 1872 and, according to the 1881 census, it and the other terraces along Chisenhale Road were home to men `at the docks’, `scholars’ (boys and girls till at least the compulsory school age of 10) and women engaging in all sort of odd-sounding occupations: button polishing, ribbon cutting, feather dying. The docks would last for almost another century, but these cottage industries would die a quick and sudden death, to be replaced with small factories making lead soldiers, shoes and board games like Bagatelle. A veneer factory just down the road would go on to produce Spitfire cockpits during WWII.

In the recent past, time was too short for me to tarry in the bedroom; the chair by the window overlooking Chisenhale Road served as a repository for unironed shirts or a place to tie my shoes in a hurry. Now (and for reasons that need not be explained here) time weighs as heavily as it does awaiting a washing cycle to end in a laundrette. Now I can sit and watch, with no distractions.

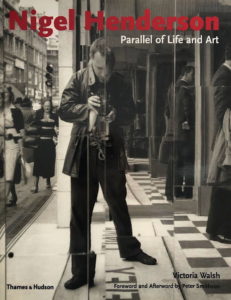

When I look down, sometimes I see a street alive with groups of children in vintage clothing jumping rope and playing hopscotch. Other times it’s residents setting up tables and hanging decorative bunting, images somehow distorted and `stretched’. They’re not my memories, but images taken and etched into my mind by the surrealist photographer Nigel Henderson, who lived three doors down for nine years from 1945. If I squint, I can just see him and his best friend, the artist and sculptor Eduardo Paolozzi, again sitting on chairs in the middle of our road.

When I gaze to the east, I might spot a woman dressed in comic-book Victorian garb – all bonnet and bustle – hobbling along the street. That would be Harriet Beecher Stowe, the American novelist and reformer, whose 1851 anti-slavery novel is memorialised for all time on a plaque at No 8, a terrace called `Uncle Tom’s Cabin 1860’. Stowe visited England in 1853, where she was lionised by the public – more than a million copies of her novel had been pirated here and were selling for 6d – and received by Queen Victoria. She returned twice in the same decade. Was the builder of the terrace a fan? An abolitionist? A displaced American? We would love to know.

And if I look through the back window and across the canal to Victoria Park, I can just make out the top of the pink-marble Angela Burdett-Coutts Memorial Drinking Fountain and its cherub fonts, financed in 1862 by the eponymous heiress to provide poor East Londoners with clean drinking water. She also funded causes as diverse as trade schools for former prostitutes and Charles Babbage’s `calculating engine’, a prototype of the computer. For these reasons and her somewhat racy later life (she married a 29-year-old American in 1881 at age 67) she is idolised in East London.

A trendsetting photographer. An anti-slavery novelist. A reform-minded philanthropist. They’re just three people within my ken from my window, helping to remind me once again that it’s not all so bad, great people do great things, that – to borrow a line from that old poem `The Desiderata’ so popular in the late 1960s – `despite all its sham, drudgery and broken dreams, it is still a beautiful world.’

This is London from my window. Look out yours from time to time. You’ll be astonished at what you see.